There’s not too much about pretentious artists that hasn’t already been explored, but even by the breed standard, abstract expressionist Mark Rothko — as depicted in John Logan’s Red — takes the cake.

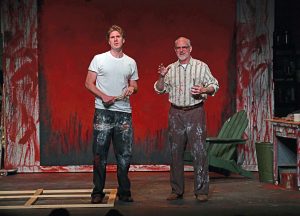

“I’m fascinated by me,” Rothko (played by Jeff Williams) chirps in the Depot Theatre’s second production of their 2022 season. The thing is, we’re fascinated by him too, as he rants, browbeats, erupts, interrupts, insults, and self-glorifies his way through two years spent in his Bowery studio in the late 1950s.

Rothko, a Russian Jew who immigrated to America in 1913, gained acclaim for his fields of color, and the intellectual battles contained therein. Red is based on actual events, following a storyline that is compelling in its own right, but also one that helps us understand what’s so special about red rectangles.

Those with a masters in art history may find some of the dialogue sophomoric, but for the rest of us it’s a fascinating window into the agony and the ecstasy that goes into the creation of art, and why it leaves so many of the great ones spent.

As the show opens, Rothko has just hired a young assistant named Ken (Michael Glavan), a budding artist himself, who is so intimidated by the great master that he can scarcely spit out a full thought.

Rothko is focused on a new and lucrative project, painting a grouping of works for the Four Seasons dining room in New York’s Seagram’s Building, a job Rothko was tasked with in real life. This will, you can feel it, turn into an examination of Rothko’s motivations for taking the job — money? Immortality? One last desperate grasp at relevance in a world where abstractionists are being shoved aside by those vulgar pop artists?

But that can wait. Meantime there is much to hash out between teacher and student, as their relationship develops and becomes more complex.

In this two-person cast, both Williams and Glavan are superb. Somehow, Williams is able to portray Rothko as insufferable, but still kind of likable. Americans have always tolerated jerks, so long as the jerk in question has purpose.

Even as Rothko insists that Ken is nothing more than an employee, he is imparting valuable lessons in everything from color to philosophy. At first Ken is baffled. Then, aided by Rothko’s incessant but instructive verbal chainsaw, a change washes over the protege’s face as he begins to crack the code.

Nietzsche was a particular influence on Rothko, particularly the duality between the staid and orderly Apollo and party-on festivities of Dionysus, which Nietzsche characterized as giving birth to tragedy.

This duality is cleverly represented in the Depot’s set, the orderly blocks of color in Rothko’s finished work contrasting with sloppy stains and smears of red and black—the colors of life and death. In one of Rothko’s most impassioned monologues, the red smudges on his face conspire to make his bluster sound a bit silly.

Ken at first is tentative, as one would be walking on a beach riddled with land mines, doing his best not to answer pointed questions in such a way as to invoke a fresh outburst of wrath.

But Glavan skillfully injects confidence into his character as time passes, and by the end, is capable of giving as good as he gets.

But Glavan skillfully injects confidence into his character as time passes, and by the end, is capable of giving as good as he gets.

This is marvelously entertaining stuff, as the two go at each other like Ali-Frazier. Just when one has been verbally pummeled to the point of being counted out, the other returns to his feet with a flurry of counterpunches.

After the philosophy and art lessons subside, the focus shifts from surveys of Matisse’s The Red Studio and Rembrandt’s Belshazzar’s Feast to Rothko’s own work, notably the Seagram Building’s murals. Rothko’s self-perceived paradox is that he is creating work that’s so ingenious, no one outside a select few are worthy of gazing upon it.

Definitely unworthy are the loud, self-absorbed cretins who eat at the Four Seasons and buy art not because they have a clue what it’s about, but to boost their own status. Rothko goes after them with a rapier, sounding much like George Carlin at his most cantankerous.

But Ken isn’t buying Rothko’s justifications for taking the job. Not that Rothko takes this assault well, but at some level he seems to delight in being challenged by someone whose intellect he has personally cultivated.

In the end, Rothko has a decision to make, one that must have worn on him for a considerable amount of time, and caused him to evaluate and re-evaluate Nietzsche’s notions of tragedy.

And, dare we think, did the inner conflict cause Rothko to think about someone besides himself, specifically the young man who got the mental ball rolling? That artists are complex is not news. But Red goes beyond superficial contradictions and gets us to think not just about art, but an artist’s place in the world — and maybe even our own. Is our greatest work that of which we are most proud, or is our greatest work those who we teach to carry on after we are gone?

The show runs until August 7, 2022. GET TICKETS NOW!

Tim Rowland contributed this review by the request of, and in collaboration with the Depot Theatre. Rowland is a journalist and New York Times bestselling author, whose humorous commentaries explore an eclectic variety of subject matter, from politics to history to the great outdoors. He and his wife Beth live on the Ausable River in Jay, N.Y.