“WORKING’s goal is to elevate the worker, making us see the person instead of the job.”

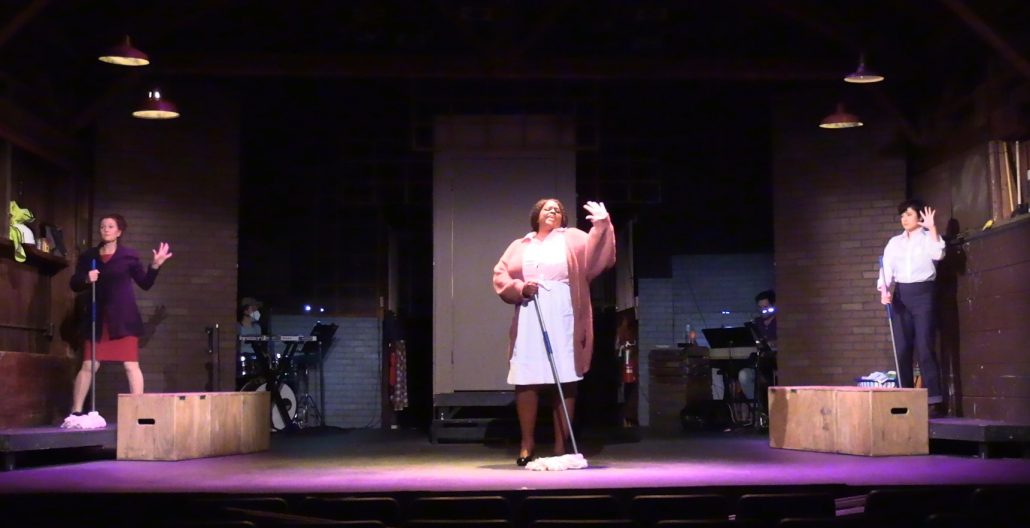

Kenney Green (center) drives the number “Brother Trucker” along with Xavier Reyes (L) and Terry Lewis in Depot Theatre’s WORKING: A MUSICAL.

The Depot Theatre had planned its production of the Broadway musical Working back in the dark ages of 2020, which was only one year ago, yet in some ways seems like a million.

As live theater was succumbing to COVID regulations last summer, it would have been impossible to forecast that Working would in some ways be a beneficiary, since its granular examination of the American labor scene has become wildly relevant in the meantime.

WORKING is based on a book by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Studs Terkel, who, before oral histories were really a thing, let average employees tell their own stories in their own words.

His 1974 book “Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do,” explored a broad cross section of jobs, from the thrilling to the mundane, and, if you squint hard enough, you can see some seeds of what has come to pass some half-century later.

Between 2020 and 2021, the modern-day labor force has been transformed, or if that’s too strong a word, at least shaken to its core by too many unsatisfying jobs chasing too few people who are still willing to do them.

Kenney Green, producing artistic director for the Depot Theatre, likes to choose works that have social relevance, and events of the last 16 months have given WORKING just that, and then some. Laments that are 50 years old sound perfectly fresh today. Art has figured out a puzzle that has bedeviled science.

Director Julie Lucido takes full advantage, giving the production a poignancy fitting with the times. Xavier Reyes, who is delightfully funny — young enough that the gravity of a dead-end job seems not to have quite registered yet — plays fast food worker Freddy Rodriguez, as the remaining cast runs in circles delivering meals in cat-chasing-tail fashion, giving a distinctly modern feel to a show that, at its inception, could never have anticipated Uber.

WORKING requires actors to step into multiple roles, representing jobs that are primarily, but not exclusively, the type we think of as being low pay and low reward. This can be tricky, but the cast never misses a beat — Terry Lewis, for one, is just as convincing as a hedge fund manager as he is an ironworker.

These scenes play off each other and blur the lines of what we might think of as legitimate and illegitimate careers. From across the stage a fundraising socialite (Amy Fitts) and sex worker (Brandi Chavonne Massey) ruminate on their careers in a way that leaves us wondering which really has the worse end of the deal.

Terkel’s book was published long before the modern day political catchphrase “dignity of work,” but as the laborers tell their stories, dignity, or at least a sense of recognition, is what they seek. It is hurtful to be thought of as “just” a laborer, or “just” a waitress.

As a peppery waitress who wants to excel, Fitts soars in dance, her heavy black shoes the only reminder that for most of us, her job is anchored to the ground in thankless drudgery. When Green, who takes the stage himself in this production and is central to two of the more memorable scenes, appears as a UPS driver, he cheerfully reports that it is the random topless sunbather who gets him through the day.

Yet when Green takes the role of retiree looking back on his life, his fulfilling memories are of the time spent with friends and family — work, not so much.

Maybe that’s for the good. WORKING shows the risk in being defined by one’s career. Fitts tugs at the heart playing the role of a pinched schoolmarm, whose eyes shine when she speaks of teaching children, then dull with confusion and bitterness at a world that has passed her by, as the old order of things, which included segregation and corporal punishment are no longer tolerated.

So too does promising young actor Thani Brant make us wonder what is to become of the factory drone who is no more appreciated than a piece of equipment. Her laugh at her position is dry and mirthless, and she makes us feel the injustice of one who has reached a dead end at such a young age.

Still, WORKING never feels heavy or depressing. It is in the main a story of resilience, and of people who have faith in themselves even if no one else does.

The score of WORKING is not as memorable as longer lasting productions, but it has its moments, and when Massey starts to sing, time stops. Lucido’s choreography is notable, be it the light playfulness of those who have not been worn down by their work, or the heavy metal-on-metal robotics of those who have.

WORKING did not last long on Broadway, but perhaps the greater question is how it arrived there at all. More social commentary than mindless entertainment, at first blush it is almost as improbable as making show tunes out of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.

Yet without the art of music and dance, Terkel’s oral histories might sink of their own weight. WORKING’s goal is to elevate the worker, making us see the person instead of the job. Next time we encounter a waiter or a truck driver, instead of seeing a waiter or a truck driver we may instead see a life. And, as we have learned over the past year and a half, that’s what’s important.

——————

Tim Rowland contributed this review by the request of, and in collaboration with the Depot Theatre. Rowland is a journalist and New York Times bestselling author, whose humorous commentaries explore an eclectic variety of subject matter, from politics to history to the great outdoors. He and his wife Beth live on the Ausable River in Jay, N.Y.